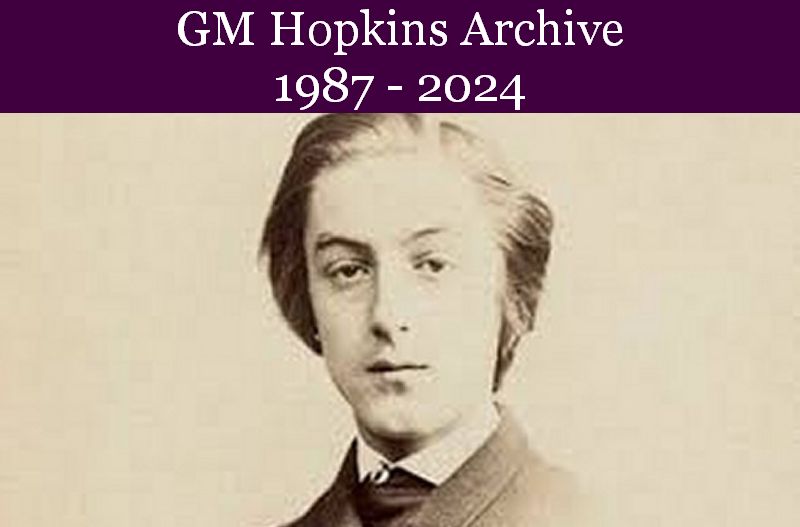

Lectures from Hopkins Literary Festival July 2023

Hopkins and the Catholic Death

Eamon Kiernan,Magdeburg University,

Germany

Paper presented at the GM Hopkins Literay Festival,July 25th 2023.

Introduction

An abiding fascination with death can be identified in the writings of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Easily taken for a sign of pathological morbidity, the poet's interest in death can also be read more positively. It bears witness to his awareness of a fundamental human challenge posed by death and of his deployment of his intellectual and artistic gifts to try to meet it. Hopkins's understanding of death is apocalyptic. By 'apocalyptic' I mean more than a recourse to the imagery of the Book of Revelation, though this, too, has importance. As will be shown, apocalyptic thought reaches beyond temporal finality, however it may be conceived, to anticipate a moral finalisation of the person which is transformational towards the present moment.

Hopkins's apocalyptic view of death shows itself with perhaps the greatest consequence in those few works which make the actual event of death a primary concern, as opposed to the figuration of mortality in general, and which, moreover, leave in place the ordinariness of dying, as opposed to portrayals of the exceptional deaths of saints and martyrs. There are three such works, which I will deal with in turn. The so-called 'Meditation on Death' from Hopkins's spiritual writings represents a systematic exposition of his understanding of Catholic teaching on death. Two major poems address the actual deaths of persons who died without evident distinction and derive much of their poetic force from the very ordinariness of those deaths. These are 'The Loss of the Eurydice' and 'Felix Randal'. In foregrounding ordinary death, the three works reflect a central concern of Hopkins's priestly ministry.

'Meditation on Death'

Probably written in 1882 in preparation for a parish mission,[1] the 'Meditation on Death' (CW v, 531-541) is structured in the Ignatian manner.[2] A twofold introduction on the paradoxical predictability and unpredictability of death is followed by a vivid imagining of the "terrors" and "comforts" of death (532, 535), and by exhortations for moral action. The 'terrors of death' are threefold: firstly, the loss of the worldly goods that one is attached to; secondly, a special kind of pain, both physical and mental, which incorporates the fear of the loss of bodily existence and the perhaps greater fear of the coming judgment of God; and thirdly, death's ominous unpredictability, which places the sin-prone human person in danger of dying in a state of sin, which may lead to damnation. The 'comforts of death' are also threefold: firstly, the Sacraments of Penance, Holy Communion and Extreme Unction; secondly, the personal Act of Contrition, which can procure the forgiveness of sin if the Sacraments are unavailable; and thirdly, supernatural hope for forgiveness, which can be effective even if the dying person is too weak to make an Act of Contrition. Hopkins then turns to the question of how to prepare oneself for a good death. Two central recommendations are made: firstly, to live a good life and live it in the fear of death; and secondly, to take steps to obtain the so-called "Grace of Final Perseverance" (538). The pious acts which can help towards the reception of this Grace chiefly include the cultivation of hope for salvation, specific prayer for the Grace, taking Communion with the intention of receiving the Grace, concern for the salvation of others and almsgiving (538-539).[3] Insisting on God's “special providence over death" (539) which is "always in our favour" (540), Hopkins concludes with the admonition to hope and pray constantly for a good death and, at the same time, quoting St. Paul to "work out your salvation in fear and trembling" (540).

Hopkins's 'Meditation on Death' has been read as a "treatise on ars moriendi" which illustrates a speculative and philosophical approach to the experience of temporality.[4] However, a consideration of the text types characteristic of Catholic works of ars moriendi reveals a need for greater differentiation. These works, which typically consisted of pictures and short texts tailored to the expected needs of the deathbed, were first created for those ministering to the dying, and, in a Jesuit innovation, for the use of the dying themselves.[5] As was mentioned, Hopkins's 'Meditation' appears to have been written for a parish mission, probably as an address to a congregation. It is tailored to persons in the thick of life who are believed to be in need of a reminder of the permanent imminence of their death, even if death seems far away. Hence, it seems better to assign it to a sub genre of ars moriendi where generalised doctrinal instruction takes precedence over the consolation of a dying person. Given that much in the 'Meditation' repeats what is found in the works of other authors, its content can hardly be termed original.[6] Philosophical speculation, then, is outweighed by the exigencies of instruction. The teaching it expounds, while it no doubt represents Hopkins's firm beliefs, is very much a standard expression of Catholic doctrine from the Nineteenth Century.

Today, the words 'fear and trembling' might convey no more to a parish audience than a paralysing terror before the judgment of God; the connotations of 'reverence', 'alertness to conscience' and 'love' are all too easily overlooked.[7] Since Hopkins's time, a tendency to over-emphasise Divine Justice at the expense of Divine Mercy has been overcome in Catholic spiritual life by St. Thérèse of Lisieux.[8] Therefore, the knotting together of religious trust and the psychological fear of condemnation inherited from the theology of the Counter-Reformation has no force of necessity. The insistence of the 'Meditation' on death's unpredictability, which lends to death a sudden, irruptive quality, helps to explain the weight given to the 'Grace of Final Perseverance'. The doctrinal formulation of Final Perseverance goes back to Saint Augustine, some of whose positions on the relationship between Grace and Nature, which had been disputed by the so-called Semipelagians of the 5th and 6th Centuries AD, were affirmed by a Gallic Church Council. Almost a thousand years later, the doctrine was restated and reaffirmed against the Protestant reformers by the Ecumenical Council of Trent (1545-1563).[9] Here, it is enough to note that according to binding Catholic doctrine, perseverance in the Christian faith into the moment of death requires a special Grace. This Grace is impetrative rather than meritorious, That is to say, it cannot be earned; it is a free gift of God, for which one may and should ask, but of which there can be no certainty.[10]

At issue in the conception of death that underlies the 'Meditation' are the lessons to be drawn from the Christian concept of Apocalypse in its relation to personal death. In apocalyptic thought, the End Times and the Last Judgment are presaged by the Particular Judgment of the individual soul.[11] To elaborate, death appears as the sudden and final confirmation or denial of the acquisition of the form of Christ in personal life, of which every moment of willed life prior to death is anticipatory. The looming threat of the End Times at every moment together with the uncertainty of the 'Grace of Final Perseverance' leads to a paradoxical rule of life: one must strive at every moment to attain and preserve a state of Grace, while relying not on one's own power to do so, but on Grace. Assuming the contemporaneity of the reception of the 'Grace of Final Perseverance' and the moment of death, though this does not seem certain, it is likely that the moment of death will be accompanied by a final trial of faith, in which the temptation to withdraw trust from God and rely on self rears its head one last time.

As the following will show, a consideration of Hopkins's apocalyptic conception of death, which is eminently Catholic, can help towards a satisfactory reading of the poems 'The Loss of the Eurydice' and 'Felix Randal'.

'The Loss of the Eurydice'

When HMS Eurydice, a naval training vessel, foundered off the Isle of Wight on March 24, 1878, Hopkins, who had been ordained to the priesthood a few months earlier, was combining the pastoral work of a priest with teaching duties at Mount Saint Mary's near Chesterfield.[12] The news of the disaster, with its heavy loss of life, "worked on" him, as he wrote to his friend, Robert Bridges (CW i, 179). The result was a long poem in sprung rhythm and tetrameters,[13] of which the same letter, comparing it to the earlier 'The Wreck of the Deutschland' (MW 110-119), attests a predominance of narration over lyrical expression and a struggle for greater intelligibility. Where the 'Wreck' explored the meaning of the extraordinary death of an unnamed "tall nun" (l. 151), 'The Loss of the Eurydice' (MW 135-138), though no less beholden to tragic violence, concentrates on the ordinary death of ordinary persons. Wrestling with 'God's providence over death' in the worst-case scenario mentioned in the 'Meditation', 'The Eurydice' draws on apocalyptic thought to show how God's providence can 'work in our favour' even when death occurs without spiritual preparation.

In the poem, death appears as a sudden, irruptive event to which the poetic voice responds with a moral advocacy for lives lost and with the insistence on the viability of hope for final perseverance. Two of the dead are singled out for attention: the captain, who is praised for going down with his ship, and an unnamed floating corpse, whose physical features are praised as a representation of seamanly excellence. As Captain Hare struggles to save his vessel, death comes upon him as a voice of truth. His acceptance of his fate is framed as a choice reduced to the starkest essentials of right and wrong, on which the poetic voice bestows the moral accolade of "righteousness" (l. 56). The striking beauty of the floating corpse depends on the marks left on his body by the hard physical work of a sailor. These reveal so persuasive a symmetry between the body, the sailor's past nautical tasks, and the working of sea, wind and light (ll. 74-80) that the poetic voice can suggest that the seaman's commitment to duty constituted one of the formative forces on his beauty (l. 78). 'Righteousness' and 'beauty', we may note, are qualities which are attributed to Christ.

In the portrayal of the ship's captain, we also find reference to the finalisation of the moral form of the person in death, to a final trial of faith, and, indirectly, to the 'Grace of Final Perseverance'. What comes to finalisation is neither the stable form of Christ achieved through a doctrinally secure faith nor its opposite, but the tenuous link between beauty and a person's duty. Captain Hare, we are told, went to his death tempted by, if not abandoned to, despair (ll. 46-47). The captain's acquiescence in his inescapable death, given in the self-sacrificial pursuance of his duty, we are encouraged to read as a sign of the last-minute overcoming of despair and of the granting of the all-important Grace. The will to duty and the formulation of the appropriate bodily acts take the place of a formal prayer.

The strange theodicy attempted by Hopkins in the 'Eurydice', which some scholars have found unconvincing,[14] can attain a greater plausibility if reference is made to the Orphic 'underthought' of the poem. The 'underthought' of poetry, as Hopkins later wrote to A.W.M. Baillie in the context of his studies of Aeschylus, is "conveyed chiefly in the choice of metaphors, etc.", as distinct from the 'overthought', "which might for instance be abridged or paraphrased ...” (CW ii, 564). As James Finn Cotter has pointed out, Hopkins, who was strongly drawn to mythic thought, and to Classical myths, in particular, saw Jesus Christ foreshadowed, though imperfectly, in Greek Gods and heroes, and he made reference to them in many of his works.[15] Though Orpheus does not appear by name in the 'Eurydice', Hopkins's choice of the word 'loss' rather than 'wreck' in the title establishes a correspondence between the shipwreck and the fate of the Greek singer-poet which is then reinforced by the reference to the ruined shrines of England.

The story of Orpheus is well known.[16] Unwilling to accept the untimely death of his wife, Eurydice, Orpheus charms his way into the underworld by song to try to save her, as in better days he had charmed the things of nature and made them sing, and leads her back to life. At the last moment, he disobeys the stricture not to turn around and look at her, and Eurydice is once more lost to death. Orpheus, too, is lost. Having burdened himself with a salvific task too great for him to accomplish, he loses his artistic gift, his sanity and eventually his life.

In the 'Eurydice', Orpheus's outcry against death is reflected in the attitude of deploration adopted by the poetic voice and in the reference made to the bereaved women and the value of their mourning. Unlike Orpheus, Hopkins's poetic voice accepts God's providence over death in its entirety, even if it does not seem to 'play in our favour'. No attempt is made to defend the justice of God in allowing death and destruction to prevail. No attempt is made to argue a case for or against God on behalf of persons who die violently or who die before their time. The deploration of the disaster is directed towards apostasy alone. In contrast to the failed mission of Orpheus, the 'concern' the poetic voice shares with Christ for the salvation of the victims of the tragedy is not invalidated in its performance; he is able to look back on the lives lost and on the women who grieve for them and find cause for a hope that encompasses the dead and the living. Orpheus in his role of seer and singer is alluded to again in the references to England. The piling of resonant place-names from the Isle of Wight, as the north wind builds up there (ll. 23-32), underlines the poet's deploration of England's apostasy (ll. 86-104). Here, the poem hearkens to a spiritual golden age when the Marian shrines were well cared for, and the natural world did not lull the pilgrim into a false sense of security, as was done to HMS Eurydice, but obeyed Christ, the better Orpheus, in providing sure guidance for the journey.

The prayer counselled by the poetic voice to the grieving women can be understood as a retrospective prayer for the 'Grace of Final Perseverance' (ll. 111-116). Grace is prayed for now for the case that it was wanted then. If the beaten and broken men had wanted the all-important Grace but had been unable to ask for it, the women can ask in their places, retrospectively. Concern for the salvation of others, which the 'Meditation' identified as a means of disposition towards the reception of the Grace, seems to work reciprocally to include the women together with their men. Here, the significance of the admonition to "crouch" (l. 110) becomes clearer. Though unusual as a posture for prayer, crouching seems wholly appropriate in the world of the poem. Crouching, in contrast to kneeling, carries the mark of the violence of the storm, which the women, despite the separation of place and time, can share with their men. In this way, the women's grief, being right to the duty of love, can be helped bodily towards righteousness. Finally, the posture of crouching allows the assent to the perhaps unpalatable truth of the uncertainty of the final perseverance of their men to be inscribed in the bodies of the women. Being right to religious duty, and again potentially beautiful, their crouching may help the bereaved women to become Christ-like themselves.

What 'worked on' Hopkins when he heard of the fate of HMS Eurydice, what he tried to make intelligible to his readers, was the paradoxical oneness of the concern of Christ for human flourishing and Christ's lordship over the irruptive power of death. The result is a theodicy which is based on the apocalyptic meaning of death, as outlined above. In his figuration of the moment of death for the persons in his poem, the poet looks to their use of moral freedom. More specifically, he considers how everyday duty might prepare an opportunity for a person to acquire the form of Christ when he is surprised by sudden death. The nexus between duty, righteousness and beauty is further developed to open a perspective on the graced mutuality of the dead and the living. In consequence, a hope for salvation is upheld which appeals to the agency of Christ present apocalyptically at the moment of death. Where salvation seems almost impossible to a doctrinally instructed mind, supernatural hope can become the efficacious act of asking to which the 'Grace of Final Perseverance' is the promised answer.

'Felix Randal'

On 31 April, 1880, in the parish of St. Francis Xavier in Liverpool, a blacksmith named Felix Spencer died of tuberculosis. The slum area where Felix had lived and died was under the pastoral care of a newly appointed “Select Preacher” or junior curate, Father Hopkins.[17] In 'Felix Randal', a sonnet in sprung rhythm using alexandrines with outrides,[18] which has been counted among his finest,[19] Hopkins remembered his pastoral visits to the ailing and penitent blacksmith. Neither the known biographical details nor the evidence of the poem itself point to a friendship between Father Hopkins and Felix Spencer.[20] They suggest, rather, that the mutual regard at the centre of the poem, if it was not a poetic creation alone, may have required some self-overcoming.

In the opening line, the news of Felix's death evokes a laconic, almost dismissive response from the poetic and priestly voice (l. 1). This gives way to a touched heart and a mutual cherishing which is aligned with the sacramental restoration of body and soul. The physical prowess of the blacksmith, whose seeming excesses, his "more boisterous years" (l. 12), are gently reprimanded (l. 8, l. 12), is returned to him in the final tercet. Felix is imagined at work on a shoepiece which will transform a carthorse into a warhorse for a mythic battle of good against evil (ll. 12-14). Through the use of the word 'sandal' for the shoepiece (l. 14) and the setting of a rhyme between 'Randal' and 'sandal', both Felix and the transformed horse are associated with the triumphant Christ of the Second Coming.[21]

In 'Felix Randal' the poetic voice conceives of Felix's death in accordance with the portrayal of death in the 'Meditation'. The qualities of unpredictability and irruption are seen in Felix's struggle against illness, which gives way to brokenness (l. 5). The 'terrors' and the 'comforts' of death underlie the portrayals of Felix's physical and mental decline (ll. 3-5) and the priestly ministering to the dying man (ll. 6-8). Indeed, Felix's response to his experience of brokenness at his end is noted with precisely those details that would make the gift of the 'Grace of Final Perseverance' seem more probable. The anointment of Felix with the oil of Extreme Unction marks the cessation of his angry rebellion against his lot, and he can die in good moral health (ll. 5-6). A previous reception of the Eucharist as Viaticum had already initiated a change for the better, in which the supernatural virtues of Faith, Hope and Charity ("a heavenlier heart", l. 6) had already begun to grow stronger. In emphasising the restoration of spiritual life to Felix in the midst of his continuing brokenness, the poetic and priestly voice also emphasises the attainment of the disposition necessary for the reception of the all-important Grace.

The spiritual transformation of the blacksmith and the horse in the final lines of 'Felix Randal', which has been termed 'apocalyptic', can be read as an example of the pervasive influence of the Book of Revelation on Hopkins's poetry.[22] However, the use of the term 'apocalyptic' in the meaning clarified above requires a movement of transformation from the eschatological future towards the present moment of lived time, that is towards the blacksmith through the anticipation of his death. As I will try to show, the mutuality established between the blacksmith and the priest allows 'Felix Randal' to be considered in this way.

Both the blacksmith and the priest are conceived of primarily in terms of their professions. Deploying a figure already met with in 'The Loss of the Eurydice', the poetic voice looks to Felix's commitment to his professional duty to give moral shape to his person. As in the portrayal of the floating corpse in the 'Eurydice', beauty is perceived in Felix's broken body and is attributed to the enduring physical mark of his work at the forge. In placing the focus not on Felix's personality but on his "mould of man" (l. 2), the poetic voice postulates a fidelity to profession as vocation through which the Christ-like form of his person called to him through the routines of his work and, despite the moral risks of his 'more boisterous years', was confirmable at every moment by his death.

Similarly, in the self-portrayal of the priest voiced by the poem, it is the 'mould of man' specific to the priestly ideal that comes to prominence: a self-emptied other Christ, who conducts himself with self-effacement. Accordingly, the 'tendering' of the sacrament, which contains the word 'tender', in the meaning of kind or gentle, and allows the warmth of empathy to colour the memory of the sacramental setting, is constrained by impersonality and selflessness. Here, the chiasmus of 'touch' and 'tears' is worth noting (ll. 10-11). The comforting touch of the priest, presumably as he wipes tears from the blacksmith's face, and which must be considered external to the sacrament, is separated from a personal subject pronoun,[23] and thus from human agency. Because the ownership of touch is sacrificed thereby, the sacramental setting is poetically widened so that the emergence of kindness and empathy through touch can only be attributed to Christ. In this way, the mutuality of 'us', 'my', 'thou', 'touch' and 'tears' (ll. 10-11) draws proleptically on the final tercet. The transformation it portrays works from the future into Felix's present.

A further poetic instrument, the meticulous use of sound patterning, allows the “fatal four disorders” which ended Felix's life to be perceived together with the allusion to Christ of the close of the poem. The prominently stressed “four” (l. 4) with the consonantal and vowel rhymes of “disorders” (l. 4) and “drayhorse” (l. 14), bring together the number four and the transformed and transforming carthorse. Different referents have been proposed for Felix's 'disorders', none of which can claim to be conclusive.[24] Given the widespread influence of Revelation on Hopkins's poetry, which was noted above, it does not seem too fanciful to to try to relate the 'disorders' to that New Testament book, and, in particular, to the Four Horsemen of Chapter 6. The Horsemen, who appear as bearers of woes which encompass a multitude of physical, psychological and moral calamities, show themselves as a collective representation of Christ who is preparing the way for the Last Judgment.[25] Through illnesses, catastrophes and death, they bring the moral form of human persons, as self-chosen through the use or abuse of freedom, to finalisation. In the full sense of the word, then, Hopkins's 'Felix Randal' can be termed an apocalyptic poem.

Conclusion

The apocalyptic understanding of death identified in Hopkins's 'Meditation' has much to offer for the reading of 'The Loss of the Eurydice' and 'Felix Randal'. In both poems, the challenge to every moment of willed life by the irruptive power of death led to the imputation to Christ of a concern for the nexus of beauty, righteousness and duty in everyday life which is finalised at the moment of death. In the 'Eurydice', the unlikely setting of the sudden death by violence of persons without evident faith gave way to the poetic establishment of the firm hope of salvation. In 'Felix Randal' the death from illness of a blacksmith from the slums of Liverpool, together with the confidence of the poetic and priestly voice in his final perseverance, opened a vista on the spiritual transformation of time and space that has a privileged place in the domain of everyday work.

The apocalyptic understanding of death is of some consequence, too, in determining how we might respond to the Catholic spirituality of Gerard Manley Hopkins. In both 'The Loss of the Eurydice' and 'Felix Randal', the poet draws on apocalyptic thought to privilege the point of inception of salvation at the moment of death through the refraction of scenes of everyday duty. It follows that a poem as much as a formal prayer can serve as an effective enactment of hope for salvation. It also follows that the exercise of Christian hope can have a wider ambit than the exclusionary formulations of doctrine might at first sight permit. Hopkins, whose Catholic faith can seem all too restricted for modern sensibilities, reaches beyond the customary limits of his confession and his time.

Notes:

[1] See "Notes for 'Instructions'", CW v, 522.

[2] See the instructions given in Exercise 1 of the 'Spiritual Exercises'. Saint Ignatius of Loyola, The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Loyola, trans, Louis J. Puhl, S.J (New York: Random House, 2000), 21-24 [§ 45-54].

[3] Catholic devotional practices such as the Scapular and the Medal of the Immaculate Conception are also mentioned (CW v, 539).

[4] Mariaconcetta Costantini, "'To his Watch': Gerard Manley Hopkins and the Rhythm of Mortal Life," The Hopkins Quarterly 39, no. 3/4 (Summer-Fall 2012): 90. Emphasis in the original.

[5] Hilmar M. Pabel, “Fear and Consolation. Peter Canisius and the Spirituality of Dying and Death.” Studies in the Spirituality of the Jesuits 45, no. 1 (Spring 2013): 2.

[6] A threefold division of points for consideration can be found in the 'Meditation on Death' by Juan Polanco, a secretary to Saint Ignatius. An emphasis on the predictability and unpredictability of death can be found in the writings of the Jesuit Saint, Peter Canisius. See Pabel, Peter Canisius, 4, 21.

[7] “Work out your salvation in fear and trembling” is a quotation from Saint Paul (Phil. 2.12). The phrase 'fear and trembling', as Gnilka notes in his commentary on the Letter to the Philippians, has a formulaic use in many places in the Old and New Testaments. It refers to the appropriate response to the encounter with the divine, from which an attitude of humble obedience towards God can emerge on the part of the Christian and the Christian community. Joachim Gnilka, Der Philipperbrief. (Freiburg: Herder, 1968), 149.

[8] John Paul II, Divina Amoris Scientia, [Apostolic Letter. St. Thérèse of the Child Jesus and the Holy Face is proclaimed a Doctor of the Universal Church], The Holy See 19th October, 1997, §8. https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/la/apostletters/1997/documents/hf_jp-ii_apl_19101997_divini-amoris.html.

[9] The Gallic Council was the Second Council of Orange (AD 529). See Engelbert Krebs, "Perseverantia Finalis," in Lexikon für Theologie und Kirche, ed. Michael Baumgartner (Freiburg: Herder 1931), 93. For the Council of Trent, see Norman P. Tanner, S.J. ed. "Council of Trent, Session 6, 13 January 1547, Decree on Justification," in Decrees of the Ecumenical Councils Vol 2 Trent to Vatican II. (London: Sheed and Ward, 1990), 676.

[10] For the difference between Impetration and Merit, see Joseph Pohle. "Merit." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 10. (New York: Robert Appleton, 1911). 15 Jul. 2023 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10202b.htm>.

[11] The term 'Apocalypse' is used here in the New Testament sense. It refers to a revelation of transcendental reality to a human person which has a transforming effect. Johannes B. Bauer, "Apokryphe Apokalypsen des Neuen Testaments," in Lexikon für Theologie und Kirche, vol. 1 A-Barcelona ed. Walter Kasper (Freiburg: Herder, 1993), 810. The transcendental reality pertains to a new ordering of cosmic and earthly life, (Achsenereignis), both individual and collective, that derives from the Resurrection, the expected End Times, the Second Coming of Christ and the Last Judgment. Karlheinz Müller, "Apokalyptik im Neuen Testament," in Lexikon für Theologie und Kirche, vol. 1 A-Barcelona, ed. Walter Kasper, 817.

[12] Norman H. MacKenzie, A Reader's Guide to Gerard Manley Hopkins. 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: St. Joseph's UP, 2008), 88.

[13] MacKenzie, A Reader's Guide, 89. Regarding the metre, MacKenzie notes stanzas of four lines, the first three with four stresses, the last with three.

[14] MacKenzie writes of a “gloomy close” which “reflects Hopkins's own disappointments”. Sobolev writes of a doctrinal anxiety leading to a destabilization of normative discourse. MacKenzie, A Reader's Guide, 94. Dennis Sobolev, The Split World of Gerard Manley Hopkins: An Essay in Semiotic Phenomenology. (Washington: Catholic U of America P, 2011), 240, 247.

[15] James Finn Cotter, "Hopkins and Myth," Victorian Poetry 27, no. 2 (Summer 1989): 171.

[16] The main sources for the myth of Orpheus are Euripides' Alcestis, Virgil's Georgics 4 and Ovid's Metamorphoses 10. I follow here the synthesizing account given in Simon Price and Emily Kearns, The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003), 394-395.

[17] Robert Bernard Martin, Gerard Manley Hopkins: A Very Private Life. (London: Harper Collins, 1991), 317.

[18] MacKenzie, A Reader's Guide, 131.

[19] The artistic success of 'Felix Randal' has been questioned by some scholars. Among recent discussions of the poem, a wholly positive account is given by James Finn Cotter, “'Felix Randal the Farrier': Visiting the Sick,” Victorian Poetry 56, no. 2, (Summer 2018). A more sceptical, though less comprehensive, appraisal is provided by Francis O'Gorman, “Hopkins' Yonder.” Literature and Theology, March 2013, Vol. 27, No. 1 (March 2013): 82-83, and by Martin Dubois, Gerard Manley Hopkins and the Poetry of Religious Experience. (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2017), 140, 149.

[20] In his Liverpool posting, Hopkins suffered from overwork, but also from a degree of alienation from his parishioners. See Martin, Gerard Manley Hopkins, 322-325. For biographical information on Felix Spencer, see Alfred Thomas, S.J., "Hopkins's 'Felix Randal': The Man and the Poem," Times Literary Supplement, March 19, 1971, 331-32.

[21] For the poem's reference to Christ as Omega through the 'sandal' for the horse, see Cotter, “'Felix Randal the Farrier'”, 206. For the identification of the horse with Christ through the association with the mythological winged horse, Pegasus, see Martin, Gerard Manley Hopkins, 329-330. As Cotter observes, a link between the horse and Pegasus had been made earlier by Marylou Motto. Cotter, “'Felix Randal the Farrier'”, 210, note 23.

[22] An early example of the application of the term 'apocalyptic' to 'Felix Randal' can be found in the seminal work of W.H. Gardner, though the meaning he gives to the term is not made fully clear. W. H. Gardner, Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-1889): A Study of Poetic Idiosyncracy in Relation to Poetic Tradition, Vol. 2 (London: Oxford University Press, 1949): 308. For the pervasive influence of the Book of Revelation, see Alison G. Sulloway, Gerard Manley Hopkins and the Victorian Temper (New York: Columbia UP, 1972), Chapter 4, and James Finn Cotter, "Apocalyptic Imagery in Hopkins' 'That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire and of the Comfort of the Resurrection'". Victorian Poetry 24, no. 3 (Autumn 1986): 261-273.

[23] I owe this observation to Valentine Cunningham, "Fact and Tact." Essays in Criticism 51, no. 1 (2001): 135.

[24] Thomas suggests “the four elements” of the ancient world and “the four humours” of ancient medicine. Whiteford advances “the four wounds of nature” due to sin which were analysed by Saint Thomas Aquinas. Marshall argues for the inclusion of a social view of the 'disorders' based on the drunkenness and violence widespread in the parish environs of St. Francis Xavier's. Thomas, "Hopkins's 'Felix Randal'," 331. Peter Whiteford. "What Were Felix Randal's 'Fatal Four Disorders'?" The Review of English Studies 56, no. 225 (June 2005): 438. Elaine F. Marshall, “Hopkins’s Sermons and 'Felix Randal: Responses to Hardship in His Urban Parishes.” Religion and the Arts 19 (2005): 325.

[25] See Akira Satake, Die Offenbarung des Johannes. Kritisch-exegetischer Kommentar über das neue Testament, Bd. 16. ed. by Dietrich-Alex Koch, (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 2008), 215-220.

Hopkins's works are quoted as follows:

Hopkins, Gerard Manley. The Major Works. Edited by Catherine Phillips. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. (MW)

Hopkins, Gerard Manley. Correspondence: Volume I, 1852-1881. Edited by R. K. R. Thornton and Catherine Phillips. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. (CW i)

Hopkins, Gerard Manley. Correspondence: Volume II, 1882-1889. Edited by R. K. R. Thornton and Catherine Phillips. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. (CW ii)

Hopkins, Gerard Manley. Sermons and Spiritual Writings. Edited by Jude V. Nixon and Noel Barber, S.J. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019. (CW v)

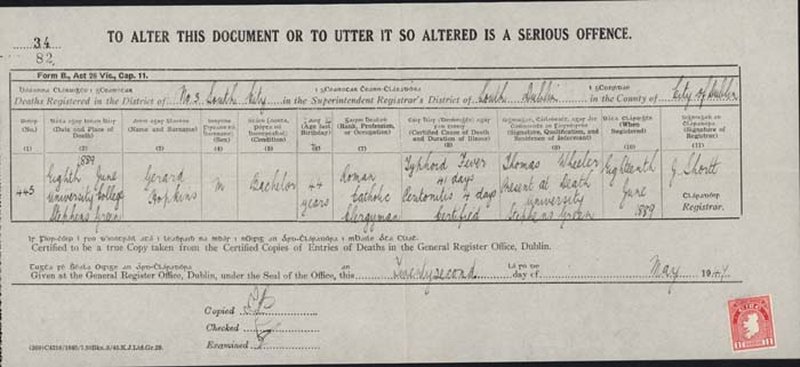

The Death of Gerard Manley Hopkins

How Did Gerard Manley Hopkins Die in Dublin in 1889 at 85 St. Stephen's Green Dublin, then part of University College, following an illness of about six weeks' duration?

Patrick Lonergan

explores the situation.